Welcome

Thank you for enrolling in this Diabetes training, presented by the National Association Directors of Nursing Administration in Long Term Care (NADONA/LTC). The next few screens will explain how to move through the training. To get to the next screen you can click the forward arrow in the bottom-right corner.

Page Elements

As you progress through the course, you’ll notice that there are several items that may appear on the screen. These include text, graphics, and interaction elements. For example, sometimes you’ll see a scroll bar to the right of the text. Whenever that scroll bar appears, it means that there’s more text beyond the bottom of the screen. If you see the scroll bar, be sure to use it to view all of the text.

The Navigation Menu

On the left side of the screen, you’ll see the navigation menu. Each item in that menu represents a Module of the course. To see a list of the Units in each Module, simply click your mouse cursor over one of the Module names. This program is provided for discussion and educational purposes only and should not be used or in any way relied upon without consultation with and supervision of a qualified practitioner based on the case history and medical condition of a particular patient. The National Association of Directors of Nursing Administration in Long Term Care (NADONA/LTC), its heirs, executors, administrators, successors, and assigns hereby disclaim any and all liability for damages of whatever kind resulting from the use, negligent or otherwise, of this training. The utilization of the NADONA/LTC diabetes program does not preclude compliance with State and Federal regulation as well as facility policies and procedures. They are not substitutes for the experience and judgment of clinicians and caregivers. The diabetes program is not to be considered a standard of care but is developed to enhance the health care professional’s ability to practice.

Module 2, Unit 1: Scope of the Problem

Each year in the U.S. alone, approximately 1.3 million people die needlessly from diabetes and its related illnesses. Diabetes is a slowly building epidemic, and is considered a public health crisis in the U.S. Nearly 21 million Americans are diagnosed with diabetes today and experts estimate there are an additional 6 million who have yet to be diagnosed. Forty-one million more have “pre-diabetes.” Current preventive initiatives seem inadequate to address the problem. There has been a continuing upward trend in the number of persons who develop diabetes each year. If the present pace continues, there could be as many as 35 million diagnosed cases in the U.S. by the year 2050, a 165% increase. This module is designed to help you become aware of the extent and seriousness of the problem of diabetes in the U.S. today, along with current barriers to effective prevention and treatment.

Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Define the scope of the diabetes problem in the U.S.

- Identify some health risks of diabetes.

- Understand the financial implications of diabetes treatment.

- Describe attitudinal and educational barriers to change

| A Slowly Building Epidemic Diabetics represent 26.4% of all admissions to long-term care facilities. |

On the average over the last 50 years, the prevalence of diabetes in the U.S. has been increasing by about 5% per year. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes increases with age; among people aged 60 and over, 10.3 million (20.9% of all people in this age group) have type 2 diabetes. Admission assessments in the Minimum Data Set recorded throughout the United States during 2002 identified 144,969 residents with diabetes, representing 26.4% of all admissions. In the last 10 years there has been another 80% increase in the number of diabetics. For young people the numbers are especially alarming. Without preventive action, one in every three American children born in the year 2000 will develop diabetes in his or her lifetime. Obesity, recognized as a growing epidemic among U.S. teenagers, is closely linked with the increase in adolescent diabetes. Among U.S. ethnic groups, Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans are 1.6 to 2.3 times more likely to have diabetes than non-Hispanic Whites.

:

ESRD43% of all residents with ESRDPeriph. vasc. wounds 15% of all diabeticsLE ampulations67% have diabetes

| Disease | Impact of Concurrent Diabetes |

|---|---|

| Diabetic retinopothy | ↑ 2900% |

| Related eye disease | 7.1 million cases in 2005 to 21.4 million in 2050 |

| Hearing problem | 76% to 91% of all diabetics |

| Heart Attack | ↑ 400 – 500% |

| Cardiovascular disease | ↑ 200 – 400% |

| Hypertention | ↑ 200% |

| Stroke incidence | ↑ 250% |

| ↑ 409% if hypertensive | |

| Stroke mortality | ↑ 5220% |

| ↑ 801% if hypertensive | |

| Hip fracture | ↑ 1200% if Type 1 |

| ↑ 170% if Type 2 | |

| Sleep apnea | 36% if Type 2 diabetes |

| Cancer | ↑ 20 – 30% risk of developing cancer |

Table 1: Impact of Diabetes on Disease

More than half (60%) of hospital admissions have diabetes as a “significant causative factor.” About one-third of Nursing Facility (NF) residents have diabetes or “pre-diabetes.” At the same time, a significant number of NF residents do not have diabetes listed as a diagnosis in spite of the fact that they are taking prescribed anti-diabetes medications. Diabetes is a significant risk to life and health. It’s the primary cause of premature death and disability in the U.S. Table I shows just a few of the ways that having diabetes increases an individual’s risk of serious illness.

Predisposing Factors

Let’s consider just a few of the risks shown in the previous table. An individual with diabetes has a 400%25 to 500%25 greater chance of having a heart attack, a 250% 25 greater chance of having a stroke, and a 522% 25 greater chance of dying from a stroke, than an individual without diabetes. Vision and hearing impairment are extremely prevalent among diabetics, and more than two-thirds of persons requiring lower extremity amputations have diabetes. It’s clear that diabetes is not a trivial illness, yet less than 2% of diabetics receive optimal quality of care. Only 7.3% of diabetics under treatment achieve target glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol goals. In addition, diabetes is the leading cause of End-Stage Renal Disease. The implications are clear: diabetes is not trivial. It’s a serious condition that poses dangerous risks to the life and health of those who have it.

List of Meds Causing Hyperglycemia

- Albuterol (Ventolin, Proventil, Combivent)Antipsychotics: VERY IMPORTANT, including:

- Aripiprazole (Abilify)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Quetiapine (Seroquel)

- Risperidone (Risperdal)

Beta-blockers

Bumetanide (Bumex)

Caffeine (Caffeine in moderation may actually be beneficial in diabetes) but in large amounts can raise blood sugar.)

Calcium channel blockers

Dextromethorphan + promethazine (Phenergan DM, Phen- TussDM¨)

Echinacea

Estrogens

Gluco-corticosteroids

Hydrochlorothiazide

Interferon Lasix

Levothyroxine (Synthroid, Levoxyl)

Megestrol (Megace)

Modafinil (Provigil)

Moxifloxacin (Avelox)

Nicotine and Nicotinic acid

Niacin

Nystatin (Mycostatin)

Opiates

Phenytoin (Dilantin)

Progesterone

Thyroid Rx’s

TPN

Valproic acid (Depakene, Depakote, ER, Sprinkle)

Knowledge Check

According to estimates, what percentage of diabetics receive optimal levels of care?

- Zero

- Less than 2 percent

- Less than 10 percent

- Less than 25 percent

| Risk | Reduction |

|---|---|

| Heart Attack | 11-20% |

| CHF | 15% |

| Stroke | 17-20% |

| Renal Failure | 40% |

| Mortality | 11% |

Table II: Health Benefits – 1 Point Reduction in A1C

A one point reduction in A1C can reduce health risks significantly. Table II shows the health benefits that can be achieved with this modest reduction.

| Financial Impact Diabetes care in the U.S. today costs about 19% of the healthcare dollar. |

|---|

Diabetes care in the U.S. today costs about $150 billion annually-19% of the healthcare dollar. That figure is expected to rise to $192 billion by 2020. Expenditure associated with diabetes and related issues amounts to 27% of Medicare costs. In 2003, more than $27 billion was spent on care for End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). Diabetics miss an average of 8.3 days of work each year, compared with 1.7 missed work days among those without diabetes. This number could be reduced by 50% with effective management and education.

Barriers to Prevention and Intervention

Considering both the health risks and the financial impact of diabetes, we might expect that its prevention and treatment would be a high priority for the healthcare profession. Unfortunately, there are indications that such is not the case. As mentioned earlier, the incidence of diabetes Type 2 is on the rise. The barriers to diligent preventive and intervention care fall into two general categories: attitude and education. Changes must occur in both categories if we want to help stem the diabetic epidemic.

| Few outside the healthcare profession understand the risks of diabetes. |

The very complexity of diabetes makes it hard to address in today’s assembly-line medical culture. Its chronic nature, pre-existing conditions, and concurrent co-morbidities require a great deal of time and commitment from a spectrum of health care professionals. Moreover, the attitude of the general public and those having diabetes is a barrier. Many lack the understanding that diabetes is a serious disease that requires diligent treatment. We live in a “fast-food” nation where the nutritional value of food is trivialized. Few outside the healthcare profession truly understand the risks of the disease or the benefits of treating it. There are also aspects of ageism and cultural bias that make some segments of the population more vulnerable.

Most dangerous of all, though, is resistance within the healthcare profession: we may be tempted to overlook a potential problem. If we don’t look, we don’t have to diagnose. If we don’t diagnose, we won’t be required to test, chart, treat, and monitor.

Educational Changes

Despite the growing body of knowledge about diabetes prevention and care, we’re still not communicating clearly enough to affect change. Too many people fail to take diabetes seriously, and there’s a lack of regard for accepted standards of care among both healthcare professionals and persons with diabetes. Further, among healthcare professionals, there is a surprising ignorance of government funding available to help. Government policies support medically necessary NF visits to improve diabetes medical management, and provide diabetes medical education by Certified Diabetic Educators. In addition, funding is available to supply footwear and other diabetic supplies, and in some cases, blood glucose testing.

End of Module 2, Unit 1

Diabetes is a serious problem, but it’s possible that we’re not taking it seriously enough. For all the knowledge we’ve gained, for all the strides we’ve made in treatment, the problem is increasing at “slow epidemic” rates. The modules in this training series will help guide you to a better understanding of the disease and its co-morbidities, how to evaluate the diabetic patient, treatment options, and care guidelines.

Module 2, Unit 2:

Defining Diabetes

Diabetes can be defined as a group of disorders caused by either insufficient production or ineffective action of insulin. A person with diabetes is unable to properly metabolize food into energy, and excessive glucose remains in the bloodstream. Pre-diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome are related disorders that usually indicate a risk for diabetes. The causes of diabetes are both genetic and environmental.

Objectives By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Define diabetes

- Distinguish between Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes Insipidus

- Distinguish between Diabetes Type 1 and Diabetes Type 2

- Define hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia

- Describe pre-diabetes and metabolic syndrome

- Define Gestational Diabetes

- List diagnostic criteria

Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetes Insipidus

Diabetes comes from the Greek word for “siphon,” due to one of the most easily observed symptoms of the disease: persons with diabetes urinate excessively and experience constant unquenchable thirst. This symptom is seen in two syndromes – Diabetes Mellitus (commonly known as “sugar diabetes”) and Diabetes Insipidus.

Mellitus comes from the Latin word for “honey.” Excessive glucose in the blood overwhelms the kidneys and spills over into the urine. Physicians used to diagnose diabetes by tasting the urine for sweetness.

Insipidus comes from the Latin word for “lacking flavor.” Like Diabetes Mellitus, this form of the disorder also causes excessive urination. Diabetes Insipidus, however, is caused by insufficient production or ineffective action of Anti-Diuretic Hormone (ADH) and is unrelated to insulin production or utilization.

This course focuses on Diabetes Mellitus.

Types 1 and 2

| About 90% of diabetics are Type 2 |

Diabetes Mellitus falls into two categories: Type 1 and Type 2.

Type 1 diabetes is defined as an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion, caused by an auto-immune disorder that destroys insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. It usually presents at an early age with a rapid onset of severe symptoms. Less than 10%25 of all diabetics are Type 1.

Type 2 diabetes is defined as a group of disorders characterized by impaired insulin secretion or unexplained insulin resistance. It usually presents in adulthood (onset at about age 40 and up) and symptoms may appear very slowly – about half of Type 2 diabetics are unaware they have the disease until they are tested for it. About 90%25 of diabetics are Type 2.

These categories are described in depth in a later module.

Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia

Hypoglycemia is defined as unusually low blood sugar. Blood sugar levels below 60 deprive the cells of adequate fuel to maintain metabolic function. Hypoglycemia may be mild, moderate, or severe. Symptoms may include confusion, sweating, weakness, rapid heartbeat, and paleness. In severe cases seizures or coma may result

By contrast, hyperglycemia is defined as unusual high blood sugar. Blood sugar levels higher than 126 can cause transient or permanent damage to the cells (especially to the cell membrane). Symptoms may include extreme thirst; “fruity” smelling breath; deep, rapid breathing, weakness, lethargy, and confusion. In severe cases, dementia or convulsions may result.

Diagnostic criteria and interventions are described in depth in a later module.

Knowledge Check

- The main difference between Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes is :

- Type 1 causes low blood sugar while Type 2 causes high blood sugar.

- Type 1 is caused by an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion, and usually presents at an early age.

- Type 2 affects only a small percentage of people.

- Type 1 is caused by insufficient or ineffective Anti-Diuretic Hormone.

Pre-Diabetes

| Without preventive measures, almost everyone with pre-diabetes will develop diabetes within 10 years. |

Those who have fasting glucose levels above normal, but not in the diagnostic range for diabetes, are considered to have pre-diabetes (impaired fasting glucose). Pre-diabetics usually have no noticeable symptoms. Up to one-quarter of persons with pre-diabetes will develop diabetes within five years, and almost all will develop diabetes within 10 years, unless preventive measures are taken. For these persons, a 5 to 7%25 weight reduction can significantly reduce the risk of developing diabetes. Women who had gestational diabetes or gave birth to a baby weighing more than 9 pounds are particularly at risk for developing pre-diabetes.

Metabolic Syndrome

Often associated with pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome (formerly referred to as Syndrome X) is characterized by excessive weight around the waist, elevated triglycerides, low levels of high-density lipids (HDL), and/or hypertension. The presence of metabolic syndrome along with pre-diabetes triples the risk for heart attack or stroke, and doubles the chances of mortality in those conditions. It is also associated with an increased predisposition to thrombosis (blood clots) and chronic inflammation.

Knowledge Check

Which of the following statements is NOT true?

- A person’s health is at risk only if their blood sugar level is well into the diabetic range.

- Most people with above-normal blood sugar who are not diabetic can reduce their risk of developing diabetes by losing weight.

- People with diabetes often have high levels of triglycerides and LDL, along with high blood pressure.

- People with diabetes can have an increased risk of heart attack or stroke.

Pregnancy and Other Contributing Factors

For about 4 percent of pregnancies, the mother will develop a temporary decrease of glucose tolerance. Blood sugar usually returns to normal. This temporary form of diabetes during pregnancy is known as Gestational Diabetes. Women who are pregnant should be tested for glucose intolerance at the onset of pregnancy, at about 24 to 28 weeks into the pregnancy, and again 6 weeks post-partum.

Further, any disease or trauma of the pancreas may affect a person’s ability to create insulin. Conditions such as pancreatitis, certain viral infections, and pancreatic cancer may contribute to the development of diabetes. In addition, genetic defects of the beta cells may cause an impaired sensitivity to elevated blood glucose.

Diagnostic Indicators

| FBG | RGB | Month | GTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <110 | <139 | <140 |

| Pre-Diabetes* | 101-125 | 140-199 | 141-199 |

| Diabetes | 126+ | 201+ | 200+ |

*Note: RBG results of 140 to 199 are not considered to

indicate pre-diabetes, but rather indicate that further

evaluation is warranted.

The amount of sugar in the blood can be measured and the results used to determine whether a person has diabetes. The two most common tests are Fasting Blood Glucose (FBG) and Random Blood Glucose (RBG). FBG testing is done at the end of an 8-hour period without food, and is currently the preferred diagnostic test. The Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) is considered less reliable and has fallen into disfavor except in cases of pregnancy or as an additional test to confirm borderline cases. GTT is measured 2 hours after a dose of 75 grams of glucose has been administered.

Table III shows the diagnostic levels for each of the above-mentioned tests.

A1C

| A1C (%) | Avg. Blood Sugar (mg/dl) |

|---|---|

| 5 | 80 |

| 6 | 120 |

| 7 | 150 |

| 8 | 180 |

| 9 | 210 |

| 10 | 240 |

| 11 | 270 |

| 12 | 300 |

Hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells, can become covered in sugar (“glycosylated”) when exposed to high plasma levels of glucose. Once a hemoglobin molecule becomes glycosylated, it remains that way. Glycosylated hemoglobin is abbreviated as A1C. A buildup of A1C molecules reflects the average amount of glucose to which the red blood cell has been exposed during its life cycle. Measuring A1C provides insight into the long-term effectiveness of therapy; its level is proportional to average blood glucose levels over a period of up to three months, with the most recent four weeks having the greatest effect.

Knowledge CheckTrue or False?

Over time, occasional high blood sugar will cause red blood cells to become “glycosylated” (covered in sugar).

True

False

Conclusion

End of Module 2, Unit 2

Diabetes Mellitus (usually called simply “diabetes”) is the official name for a group of disorders related to a person’s ability to make or use insulin. Above-normal levels of glucose in the blood indicate that a person either has, or is at risk for, diabetes. There are two classifications of diabetes: Type 1 and Type 2. Both classifications depend on both genetic and environmental factors.

Diabetes is not defined by the presence or absence of symptoms. At least half of persons with pre-diabetes or Type 2 diabetes experience few or no symptoms and remain undiagnosed unless they happen to receive blood tests. Blood sugar levels, preferably tested by Fasting Blood Glucose levels, are the only reliable diagnostic indicators.

Module 2, Unit 3: Diabetes Pathophysiology

If you’ve ever driven through a mountainous region, you may have seen warning signs such as “falling rocks” or “bridge ices before road.” These signs don’t indicate that you’ll definitely encounter rocks or ice, but they do indicate a strong potential for those dangers to occur. In a similar way, diabetes has its own warning signs, known as “risk factors,” that indicate a strong potential for the disease to occur. If diabetes does develop, it can take one or both of two forms: either the person with diabetes is unable to make enough insulin, or the body becomes resistant to insulin, or both. In either case, diabetes causes long-term and potentially disastrous damage to the body’s cells through a process called osmosis.

Objectives

Diabetes causes long-term and potentially disastrous damage

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify diabetes risk factors

- Define obesity

- Describe insulin insufficiency and insulin resistance

- Understand how diabetes damages cells by osmosis

Risk Factors

There are a number of risk factors that indicate the potential for a person to develop diabetes, some of which are beyond an individual’s control. For example, a person with an immediate relative who has diabetes is at greater risk for diabetes him/herself. In addition, a person’s ethnicity may be a risk factor. Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to develop diabetes than other ethnic groups. On the other hand, some risk factors are within an individual’s control. Obesity, lack of exercise, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and high triglycerides are all associated with increased likelihood of developing diabetes, and all can be addressed with lifestyle change and/or medical treatment.

Obesity

| BMI using pounds and inches

weight in pounds *703 Inches(squared) |

| BMI using kilograms and centimeters

weight in kilograms*703 centimeters(squared) |

Obesity in particular has an influence on an individual’s risk for diabetes, and some evidence shows that those who store fat primarily in their midsections are at even greater risk. This risk may be due to accumulation of fat cells around the pancreas and liver. The standard measure for obesity is Body Mass Index (BMI). BMI is calculated as a ratio of weight to height. Figure 2.3.1 shows two formulas for measuring BMI: one using pounds and inches and one using kilograms and centimeters. Expert opinions vary slightly, but a BMI of about 24 is considered Normal. BMI of about 25-29 is considered Overweight, about 30-39 is considered Obese, and greater than about 40 is considered Extremely Obese.

Knowledge Check

Persons who are obese are at increased risk for developing diabetes. Body Mass Index is the standard measure of obesity. At what BMI range is a person considered obese?

- below 24%

- 25-29%

- 30-39%

- over 40%

Insulin Insufficiency, Insulin Resistance and Glucagon

Insulin is a hormone produced in the pancreas. It helps the body’s cells take in glucose (sugar) from the bloodstream and use it as fuel. Under normal circumstances, when the body senses an increase in blood sugar, the pancreas will automatically release insulin to the level needed. In persons with diabetes, there is not enough insulin to adequately manage the amount of glucose in the blood.

In some people, the pancreas is unable to make enough insulin (insulin insufficiency). In others, the pancreas may be making insulin, but other factors prevent the body from utilizing it properly (insulin resistance). These conditions are inter-related.<b></b> A related hormone called glucagon is also controlled by the pancreas. This hormone assists the body to store excess glucose when blood sugar levels rise and release stored glucose when blood sugar levels are low.

Cell Damage Through Osmosis

If high blood sugar is allowed to continue…cells can become seriously dehydrated.

Osmosis is the process by which fluids move from one side of a semi-permeable membrane to the other to compensate for a difference in concentration. When there is too much glucose in the blood cells, your body will attempt to dilute the blood. Water from other cells, such as muscle tissue, will move across the cells’ membrane into the bloodstream. If the high blood sugar is allowed to continue, the affected cells can become seriously dehydrated. Such dehydration can be particularly damaging to cells of the brain and to the capillary membranes of the body’s various organs.

Knowledge Check

For persons with diabetes, how does osmosis damage the body?

- It makes blood too thick to move through the body, which can lead to heart attacks or stroke.

- It causes dehydration of cells, such as those that make up organ and muscle tissue.

- It causes blood cells to become covered in sugar so they can’t oxygenate

- It prevents nutrients from crossing the membrane surrounding the blood vessels.

HHNS

The osmosis caused by continuing high levels of blood sugar can lead to a dangerous condition called Hyperosmolor Hyperglycemic Nonketotic Syndrome (HHNS). Symptoms of HHNS include high fever, confusion, loss of vision, or hallucinations. HHNS can occur in type 1 diabetics but is more often seen in type 2 diabetics. It is most frequently seen in older persons and is usually brought on by illness or infection.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

When the body’s cells are unable to access glucose for fuel, they will begin to break down fat and muscle to use for fuel instead. The resulting fatty acids, when oxidized, become ketones: strong acids that are poisonous to the body. Acetone, the chemical used in nail polish remover, is a form of ketone. Persons with diabetes type 1 are particularly at risk to develop dangerously high levels of ketones, a condition known as <i>Diabetic Ketoacidosis</i> (DKA). DKA can be life-threatening. More information about symptoms of DKA can be found in a later module.

Conclusion

End of Module 2, Unit 3

Diabetes is associated with several unhealthy and even dangerous conditions. Some of these conditions occur prior to diabetes and may contribute to its development. Others are potential results of diabetes. In addition, certain hereditary factors can make a person more likely to develop diabetes. Undiagnosed or inadequately treated diabetes can have disastrous effects. This is true for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Module 2, Unit 4: Hypo- and Hyperglycemia

As discussed in Unit 2 of this Module, hypoglycemia (unusually low blood sugar) and hyperglycemia (unusually high blood sugar) pose serious health risks. In either case, variation from normal blood sugar levels can lead to long-term damage to the body and, in extreme cases, can be fatal.

Symptoms of hypoglycemia range from shakiness to loss of consciousness. Symptoms of hyperglycemia range from headache to coma. If symptoms are present, appropriate action should be taken immediately. You will need to know how to determine the degree of variation from normal and the interventions required. In addition, you’ll find it helpful to know predisposing factors. Knowing what to watch for can help you to act quickly when action is needed.

Objectives

Variation from normal blood sugar levels can lead to long-term damage.

By the end of this module, you will be able to

- Define the blood glucose levels associated with hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia

- Take an appropriate history to include medications which may predispose an individual to abnormal blood sugar levels.

- Perform a comprehensive physical assessment when either hypo- or hyperglycemia is present

- Use critical thinking to take appropriate action to reverse hypo- or hyperglycemia

- Explain “Step Theory”

- Define “Sick Days”

- Blood Glucose Levels

Hypoglycemia is classified in three ranges, by blood glucose levels:

- Mild (51-70

- Moderate (31-50

- Severe (less than 30

Hyperglycemia is defined as blood glucose level of above 125 Fasting Blood Sugar or 200 Random Blood Sugar.

Predisposing History: Hypoglycemia

Eating irregularly or skipping meals can lead to sudden drops in blood sugar. Residents should be encouraged to eat meals at regular times.

Sudden increases in activity such as “shopping during Christmas or a New Year’s resolution to exercise to lose weight” can lead to a drop in blood sugar. Additionally, any change in medication should be followed by careful blood sugar monitoring.

If a resident experiences an acute medical condition which causes cognitive impairment such as delusions they may be unable to report signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia and therefore should be carefully monitored.

If an NPO order has been given prior to lab testing, the missed meal may result in hypoglycemia. <i>Be vigilant regarding such orders and make sure fasting is an absolutely necessary factor for the lab work being ordered.

Knowledge Check

True or False? Eating irregularly or skipping meals can lead to sudden drops in blood sugar.

True

False

Signs or Symptoms of Hypoglycemia

Depending on the level of severity, hypoglycemia and result in symptoms ranging from headache to loss of consciousness. Symptoms of hypoglycemia are listed below.

- Headache

- Shakiness

- Hunger

- Dizziness or lightheadedness, weakness

- Sweating (“diaphoresis”)

- Nervousness or irritability

- Sudden changes in behavior or mood

- Tachycardia

- Numbness or tingling around the mouth

- Pale skin

- Clumsy or jerking movements

- Confusion

- Seizures

- Loss of consciousness

Interventions for Moderate to Severe Hypoglycemia

If symptoms are present and hypoglycemia is suspected, immediately have the resident sit or lie down to prevent injury. Then test the resident’s blood glucose level. In cases of impaired consciousness, however, first administer glucose and then test blood sugar to confirm suspicion of low blood sugar.

If swallowing is difficult or impossible, administer insta-glucose or apply cake icing or sugar to the inner aspect of the resident’s gums. If no other route is available, 30 ml of syrup or honey may be administered rectally.

Repeat testing in 15 minutes and administer sugar again if needed. After two attempts to administer glucose orally, if blood sugar levels have not stabilized, 1 mg Glucagon should be administered IM. Inject the entire ampule into the resident’s upper arm, thigh, or buttocks. The resident should be made to lie on his or her side in case of nausea associated with glucagon. If there is no response within 15 minutes, repeat injection and call 911 per facility protocol.

Interventions for Mild or Moderate Hypoglycemia

Those who are able to swallow may take glucose tablets, packets of sugar, fruit juice, honey, or syrup. Once the resident is more alert additional food should be given, such as peanut butter crackers, fresh fruit, milk, a cheese sandwich or regular (not diet) soda.

Knowledge Check

True or False? Administration of Glucagon is an appropriate intervention for Mild to Moderate Hypoglycemia.

True

False

After Hypoglycemic Episode

After the episode has been resolved, continue to monitor hydration. Review the resident’s care plan and prescriptions for possible contributing factors. Notify the resident’s physician/practitioner, especially if the episode was severe (required glucagon or IV intervention).

Predisposing History: Hyperglycemia

Nicotine and excessive caffeine can raise blood sugar.

Hospitalization and its related stress may precipitate diabetes, especially in pre-diabetics. Medications and dietary supplements can also lead to elevated blood sugar levels. These fall into the following categories:

- Asthma inhalers

- Antipsychotics

- Hormones

- Blood pressure medications

- Pain medications

These medications and supplements are listed fully in the “Tips” for this page.

Tips:

In addition, nicotine and excessive caffeine can raise blood sugar, although moderate amounts of caffeine may actually be beneficial.

Meds Causing Hyperglycemia

Albuterol (Ventolin¨, Proventil®, Combivent®) Antipsychotics: VERY IMPORTANT, including:

Aripiprazole (Abilify

Fluoxetine (Prozac

Quetiapine (Seroquel®)

Risperidone (RisperdalBeta-blockers Bumetanide (Bumex®)

Caffeine (Caffeine in moderation may actually be beneficial in diabetes) but in large amounts can raise blood sugar.)

Calcium channel blockers

Dextromethorphan + promethazine (Phenergan® DM, Phen- TussDM®)

Echinacea

Estrogens

Gluco-corticosteroids

Hydrochlorothiazide

Interferon

Lasix

Levothyroxine (Synthroid®, Levoxyl®)

Megestrol (Megace®)

Modafinil (Provigil®)

Moxifloxacin (Avelox®)

Nicotine and Nicotinic acid

Niacin Nystatin (Mycostatin®)

Opiates Phenytoin (Dilantin®)

Progesterone

Thyroid Rx’s

TPN

Valproic acid (Depakene®, Depakote®, ER, Sprinkle)

Signs or Symptoms of Hyperglycemia

Some symptoms of hyperglycemia may resemble symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Depending on the severity of the hyperglycemic episode, symptoms can range from mild to dangerous. These symptoms include:

- Headache

- Poor appetite

- Extreme thirst or dry mouth

- Extreme hunger

- Upset stomach or vomiting

- Increased urination

- Worsening or new onset of incontinence or nocturia

- Fruity” smelling breath

- Weakness

- Deep, rapid breathing

- Confusion, worsening dementia

- Functional decline

- Falls

- Lethargy

- Coma

- Convulsions

Some symptoms of hyperglycemia may resemble symptoms of hypoglycemia. Therefore, always attempt to test blood sugar prior to taking action.

Therapeutic Philosophy

The goal of today’s treatment regimen is “tight glycemic control.

Auto-pilot monitoring with unaddressed, frequent elevations in blood sugar is no longer considered acceptable medical practice. Residents who are known to be diabetic or pre-diabetic should have life-long periodic monitoring at least every three months.

Insulin and/or oral medication regimens should be diligently titrated until blood glucose levels are routinely in target values (usually 90-140, or HgbA1C of 8.0 or less). This is known as “tight glycemic control.”

All interventions should be individualized. Consider oral agents that are less likely to cause hypoglycemia, for example Thiazolidinediones, Januvia, or Metformin (unless there are kidney or liver problems). Keep insulin regimens simple: consider basal/bolus approach.

In end-stage situations, the primary goal is to still relieve symptoms, and to prevent hypoglycemia and/or acute complications.

Knowledge Check

The term “tight glycemic control” means:

- Keeping blood glucose levels routinely within target values.

- Administering treatment if levels frequently fall outside the normal range.

- Administering treatment only if resident shows symptoms of hypo- or hyperglycemia.

- Determining average glucose levels over a period of time, and designing treatment for that average.

Sick Days

Any clinical change should be considered a “significant blood sugar event” until proved otherwise. Stress or illness can cause increases in glucose levels. Therefore, if a resident is depressed, has other psychological stressors, or has a fever or infection, increase glucose monitoring. Also monitor urine for ketones, and monitor and maintain hydration. Use an easily digestible liquid diet containing carbohydrates and sodium. If indicated, consider supplemental short acting insulin.

Knowledge Check

True or False? Any clinical change should be considered a “significant blood sugar event until proved otherwise.

True

False

Conclusion

End of Module 2, Unit 4

Whether too low (hypoglycemia) or too high (hyperglycemia), deviations from normal blood glucose levels can lead be harmful – even dangerous. Residents with a history of such deviations should be closely monitored, especially if any of the pre-disposing factors are present. Memorize the signs and symptoms of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia and be prepared to intervene quickly if these events occur.

Module 2, Unit 5: Diabetic Co-Morbidities

Because it injures the cell’s wall, diabetes has an effect on virtually every organ system. Some pre-existing diseases or dysfunctions are made worse by the effects of diabetes. In other cases, diabetes may be the root cause of another disease. A diabetic co-morbidity is a disease that is associated with, caused by, or made worse by diabetes.

Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Define the term co-morbidity

- Describe the relationship between diabetes and diabetic endothiliopathy

- List several ways in which diabetes causes systemic problems specific organs affected by diabetes

- Identify specific organs affected by diabetes

Mechanism of Morbidity

The primary danger of abnormal osmosis is dehydration of cells.

You may remember from unit 3 that diabetes affects the density of cells and results in abnormal osmosis. The primary danger of abnormal osmosis is dehydration of cells, particularly in the capillaries. Damage to the endothelial cells lining the capillaries is known as diabetic endothiliopathy, and can lead to abnormal passage/seepage of nutrients and waste products. This results in widespread damage to surrounding cells and alteration of cell metabolism. In addition, diabetes damages the kidneys’ baroreceptors (pressure monitors). The resulting hypertension may eventually result in hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis), which is a form of arteriosclerosis characterized by the deposition of plaques containing cholesterol and lipids on the innermost layer of the walls of large and medium sized arteries. Atherosclerosis impairs the vessel’s ability to dilate, cutting off blood supply to surrounding cells.

Knowledge Check

The primary mechanism contributing to diabetic co-morbidity is:

- Atherosclerosis due to high blood pressure

- High blood pressure due to kidney damage

- Deposition of plaques due to high cholesterol

- Diabetic endothiliopathy due to abnormal osmosis

Co-Morbidity Overview

Imagine an individual who has high blood pressure, high cholesterol and triglycerides, reduced blood flow, a compromised immune system, and problems with blood clotting. Diabetes can be a factor in each of these disorders. One alone can be dangerous; in combination they can be devastating. Therefore, the importance of controlling blood sugar levels cannot be overstated. The next few pages describe diabetes-related disorders for various systems of the body.

Immune System

Any elevation of blood sugar can suppress the immune system.

Diabetes can reduce the body’s ability to deal with infections. Any elevation of blood sugar can suppress the immune system, and a blood sugar level above 160 mg/dl impairs the function of white blood cells, reducing their ability to remove pathogens and cell debris (the process known as Phagocytosis). Diabetics have a higher risk of infections of all types, including:

- Mouth infections such as thrush and gingivitis

- Genitourinary infections such as yeast infections and urinary tract infections

- Bone infection (Osteomyelitis)

- Skin or connective tissue infection (Cellulitis)

- Fungal infection of the mouth, fingernails, or toenails

- Infection in the lungs (Pneumonia)

- Skin ulcers

Cardiovascular System

Diabetes is known to affect lipid metabolism, making diabetics more susceptible to increased levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. As mentioned above, diabetics are also more susceptible to atherosclerosis and have an increased risk of both heart attack and stroke. Furthermore, even though diabetes is often accompanied by high blood pressure, diabetics may have difficulty with sudden drops in blood pressure when they stand up from a seated position, a condition called Orthostatic Hypotension. Resulting dizziness can lead to falls. Blood coagulation disorders associated with diabetes can increase the risk of blood clots. A blood clot in a vessel or in a cavity of the heart is called Thrombosis. If that clot travels and blocks a smaller vessel, it’s called an Embolism. An embolism in the lungs (Pulmonary Embolism) can be life threatening. Poor circulation, combined with infection, can lead to gangrene in a limb and may require amputation.

Vision

Diabetic Retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among American adults.

Problems with the eyes are common for individuals with diabetes. Diabetic Retinopathy (disease of the retina) is the leading cause of blindness among American adults. More than half (60%) of diabetics have damage to the retina, although the damage may be mild enough that vision is not yet affected. This damage is progressive, worsening over time. The earliest stage is called “mild nonproliferative,” and is characterized by very small aneurysms of the retina’s tiny blood vessels. The next stage is called “moderate nonproliferative.” In this stage, some of the blood vessels become blocked. In the “severe nonproliferative” stage, more blood vessels are blocked and the retina starts sending signals to the body to grow new blood vessels. The disease then reaches the “proliferative” stage, growing new vessels that are abnormal and fragile. If these vessels leak blood, it can result in severe vision loss or blindness. Impaired metabolism can also cause increased levels of sorbitol, a sugar alcohol, leading to fluctuations of fluid levels in the lens of the eye and resulting in cataracts.

Knowledge Check

True or False? Diabetic Retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among American adults.

True

False

Gastrointestinal Tract

Older adults in hospitals or long-term care settings already have an increased risk of illness due to a particular kind of bacterium called Clostridium difficile, or “C. diff.” This is a bacterium that proliferates when antibiotics are being used to control an infection. C. diff. infections have been on the increase in recent years, and diabetics are more at risk than the general population of older adults. The effects of C. diff. infection range from mild diarrhea to swelling and inflammation of the colon (Colitis). In some cases, C. diff. can be life threatening. Diabetics may also experience a reduction in the muscle action that helps move waste through the intestines. Gall bladder disease and pancreatitis are also associated with diabetes. Pancreatitis may be a result or a cause of diabetes.

Genitourinary Tract

Uncontrolled diabetes may ultimately result in kidney failure.

As mentioned earlier, diabetics face an increased risk of infections overall. This is just as true in the case of genitourinary infections. In addition, damage to the central nervous system may make it difficult for diabetics to sense a full bladder, a condition known as Neurogenic bladder. Diabetes is also known to have lasting detrimental effects on the kidneys. Insufficient kidney function can be linked to abnormal spillage of proteins into the urine, a condition known as Proteinuria. All diabetics with proteinuria are also hypertensive. The effect of uncontrolled diabetes on the kidneys is progressive, and may ultimately result in kidney failure, or ESRD (End Stage Renal Disease).

Neurological System

Diabetes causes damage to the nervous system too. In recent years, studies have shown a linkage between diabetes and depression, particularly in women. For men, about half of those with diabetes may suffer from erectile dysfunction.

Damage to the nerves may reduce the ability to sense heat or pain. On the other hand, nerve damage may cause sensations of burning, stabbing, or tingling. Diabetics may have difficulty telling if the foot is raised high enough when walking, causing an increased risk of tripping. Constant nerve damage may also lead to a condition called Charcot’s joint, a progressive degenerative disease affecting weight-bearing joints.

Knowledge Check

Uncontrolled diabetes can have a(n)____________ effect on the kidneys:

- Lasting beneficial

- Unknown

- Progressively detrimental

- Short-term detrimental

Conclusion

End of Module 2

The detrimental effects of diabetes are wide-ranging. Virtually every part of the body can be harmed; in many cases that harm can lead to multisystem failure and may be fatal. The information contained in this training should serve as a stimulus to an increased commitment to diabetes care and treatment.

Module 3, Unit 1 Introduction

In the Module 2, you leaned about the definition of diabetes and the scope of the problem in the U.S. You also learned about diabetic co-morbidities. In this module, you will learn more about evaluating and treating the diabetic resident. This unit focuses on screening and evaluation: how to determine the resident’s condition.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Determine how often the resident should be evaluated

- State current benchmarks

- List the questions that you should ask to determine the resident’s condition

- Recognize the physical signs of diabetes

Frequency of Screening and Evaluation

Residents should be evaluated for diabetes at least every 3 years.

When the resident is being admitted from a hospital, a baseline blood glucose level is usually available. Be sure to review that information. If not, a fasting blood sugar should be part of the first baseline lab work done upon admission. Residents should be evaluated for diabetes at least every 3 years, and more frequently if BMI is greater than 25. (See Module 2, Unit 3 for BMI calculation.)

Current Benchmarks

Diagnostic benchmarks have been tightened recently as greater control has proved more effective in reducing morbidity. The next few pages detail current benchmarks for blood glucose and related diagnostic criteria

Blood Glucose

Fasting or pre-meal glucose levels should be maintained at less than 110. Two hours after a meal, levels should be below 140. Over time, A1C in the frail elderly should be kept below 8. The American Diabetes Association has even stricter recommendations, suggesting that A1C be kept below 7, and some endocrinologists recommend values lower than 6.5. The goal should be a balance between the danger of hypoglycemic episodes and the advantage of tight glycemic control. Remember, tighter control has been proven to reduce both complications of diabetes and further morbidity.

Knowledge Check

In the frail elderly, what is the target for A1C?

- less than 3%

- less than 5%

- less than 8%

- less than 10%

Lipids

For female residents with diabetes, high-density lipids (HDL) should be maintained at greater than 50. For males with diabetes, HDL should be kept higher than 40. For both males and females, aim for low-density lipids (LDL) levels of less than 100 mg/dL and Triglycerides less than 150. Recent studies have shown that reducing LDL even further, to less than 70 mg/DL, leads to an even greater reduction in acute coronary events. The risks of higher doses of statins are significantly outweighed by the benefits of more vigorous therapy in high-risk patients with a relatively long life expectancy.

Blood Pressure and Albuminuria

A healthy blood pressure for residents with diabetes is 120/80. Albumin in the urine (<i>Albuminuria</i>) is a sign of kidney damage: protein that should remain in the body is spilling into the urine. Normal levels are below 20 mg/dL. Levels between 20 and 300 are considered Microalbuminuria, an early sign of kidney disease.

Questions to Ask

Evaluation of the diabetic resident can be greatly facilitated by gathering information from the resident himself/herself. Asking the right questions can reveal issues that might otherwise take considerable time to surface. The information you should gather is roughly categorized on the next few pages.

Appetite and Thirst

Ask about:

- Recent weight loss

- Change in appetite or unusual increase in appetite

- Difficulty complying with dietary requirements

- Increased thirst

General Wellness

Ask about:

- Recent fever

- Evidence of infection

- Headaches (associated with or without meals

- Episodes of dizziness

- Episodes of nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Periodic sweats

- Peripheral numbness

- Vision changes

- Recent fundusocpic exam of the eye and results

- Increased urinary frequency

- Episodes of lethargy, anxiety or fatigue

- Any recent changes in activities of daily life (ADLs)

Medical Condition

Ask about associated significant co-morbidities such as:

- COPD

- Hypertension

- Pancreatitis

- GB diseases

- Renal failure

- Wounds

Ask also about associated medications such as

- Anti-depressants

- Anti-psychotics

- Steroids

Physical Assessment

A thorough physical assessment can reveal signs and symptoms that may be associated with diabetes or diabetic co-morbidities. A proper assessment should include baseline labs and vital signs as well as a thorough examination of skin and lower extremities.

Knowledge Check

True or False: Routine physical examination of the diabetic resident should include a thorough examination of the lower extremities.

True

False

Baseline Labs and Diagnostics

The following tests should be conducted at initial assessment:

- Random blood sugar or A1C

- Lipid panel

- Albumin

- BUN/Cr (increased Cr indicates loss of at least 50%25 of renal function

- Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR, a measure of renal function

- Liver Function (LFT)

- Thyroid Function (TSH)

- Microalbuminuria (UA) test by urine-dip strips

- EKG

- Ankle/Brachial Index (ABI)

Diabetes, as discussed in Module 2, primarily affects microvascular flow, but it can have an effect on larger vessels both directly and through its arthrosclerosis co-morbidity. ABI is the ratio of blood pressure in the arteries in the ankle divided by the blood pressure in the arm. It is used to predict the severity of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). It can provide a measure of the underlying microvascular support to the lower extremity. Testing can be done by auscultation using arm and leg cuffs, but is usually done with a Doppler device to monitor the pulse while cuffs are inflated over the brachial artery in the arm and the dorsalis pedis artery in the foot. The normal resting ABI is 1 or 1.1 – meaning that BP is about the same in both arteries. If ABI is less than .95, there is significant narrowing of one or more blood vessels in the legs. If less than .8, pain may be present in the foot, leg, or buttock during exercise. If less than .4, symptoms may occur when at rest. If less than .25, severe, limb-threatening PAD is probably present.

Observational Assessment

Check eyes for evidence of cataracts and mouth for evidence of caries or gingivitis. Examine the skin thoroughly, and conduct a skin turgor test to determine presence of dehydration. Examine the perineal area to detect fungal infection or vaginitis.

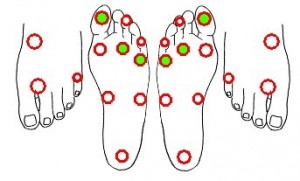

Examine the lower extremities: a basic foot exam should be repeated every 30 days. Take note of any indication of pedal edema, or peripheral capillary filling. Look for evidence of skin atrophy, lesions, inflammation or ulcerations, or evidence of toenail fungus. Evaluations for Charcot’s deformity or neurological damage may also be included. More information about lower extremity care can be found in Unit 6 of this module, Diabetic Wound Care.

Conclusion

End of Module 3, Unit 1

Initial screening and periodic evaluation of the diabetic resident can help with establishment of baseline values, early detection of problems, and prevention of more severe problems. There are several tests to conduct, but personal interaction is at least as informative, if not more so. Know what questions to ask, and take the time to make careful observations.

Module 3, Unit 2 Introduction

Although more often associated with Type 1 Diabetes, under some circumstances, Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) can occur in Type 2. If allowed to become severe, it can lead to dangerous or even life-threatening symptoms. This unit defines Diabetes Ketoacidosis and describes early and late signs.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Define Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) and its causes

- List early and late signs and symptoms

- Describe negative effects of too-rapid correction of associated dehydration

Causes of DKA

Without insulin, glucose is not transported across the cell membranes of muscle and fat cells. Thus, even though the sugar is just on the other side of the membrane, cells sense “starvation” and begin to create glucose from more complex materials. This process is called gluconeogenesis (“newly created glucose”). When stored protein is broken down for fuel, it creates a waste product called Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN). When stored fat is broken down for fuel, it creates waste products called Ketones, which acidify the blood. The resulting increase of blood acidity is called Ketoacidosis.

DKA in Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetics are less likely to develop ketoacidosis than Type 1 diabetics. Type 2 diabetics usually have some insulin production and so are able to utilize some glucose for fuel. In certain circumstances, however, the Type 2 diabetic may break down fat too rapidly. These circumstances include fever, infection, and poor fluid intake.

Knowledge Check

Ketoacidosis can occur when:

- The body uses stored insulin as fuel

- The body uses stored glucose as fuel

- The body uses stored protein as fuel

- The body uses stored fat as fuel

Early Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Ketoacidosis include:

- Sluggishness, extreme tiredness

- Fruity smell to breath, often compared to the smell of nail polish remover

- Extreme thirst, despite large fluid intake

- Excessive urination, bedwetting

- Extreme weight loss

- Yeast infections that fail to resolve

- Muscles wasting

- Agitation, irritation, aggression, confusion

Late Signs and Symptoms

Diabetic coma can occur after prolonged DKA…. speedy medical attention is imperative.

Late signs, which should be considered a medical emergency, may include:

- Vomiting

- Confusion

- Abdominal pain

- Loss of appetite

- Flu-like symptoms

- Lethargy and apathy

- Extreme weakness

- Unusually deep or rapid breathing, “air hunger” (Kussumal breathing

- Unconsciousness (diabetic coma)

Correcting Dehydration

Measures should be taken to correct dehydration and depletion of electrolytes associated with Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Care should be taken in the rate of correction. Too-rapid correction may have detrimental effects. These include

- Hypokalemia

- Cerebral edema

- Aspiration

- Pulmonary edema

- Renal tubular necrosis

Knowledge Check

True or False: Too-rapid correction of DKA-related dehydration can have detrimental effects.

True

False

Conclusion

End of Module 3, Unit 2

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially dangerous condition more often associated with Type 1 diabetes than with Type 2. Fever, infection, and dehydration can increase the probability of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Type 2 diabetics. If undetected and uncorrected, DKA can precipitate dangerous, even life-threatening, effects. Fortunately early signs of DKA are readily observable.

Module 3, Unit 3 Introduction

A resident newly diagnosed with diabetes will have many questions and concerns, and so will his or her family members. Furthermore, the resident may feel overwhelmed by the life changes that inevitably follow. This unit covers issues around educating the resident and family, and psycho-social issues in residents with diabetes.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- List benefits of resident education

- Identify the information that should be imparted to residents and their family members

- Clearly communicate the importance of risk factors and life-style changes

- Describe the monitoring that should be part of an overall care plan

- Define the term “sick day”

- Utilize two common tools for measuring depression in elderly residents

Benefits of Education

Proper education can provide many benefits. Residents who understand the implications of their decisions are empowered to make better ones. Co-morbidity and progressive pathology can be reduced, while compliance with medication and monitoring regimens can be improved.

Education Skills

Effective education is as much about how you present information as it is about what you present. Hold the interview in a well-lighted, quiet and comfortable space. Avoid having your back to a window or other bright light: doing so makes it hard for the resident to see your face and lips. Use eye contact to maintain a connection. When speaking, speak clearly and distinctly, and teach at a level the resident can understand. Do your best to mitigate language barriers. Watch for non-verbal communication and affect. Provide opportunities for the resident to communicate. Ask open-ended questions, and listen carefully to the responses. Be empathetic, respectful, and non-judgmental.

Knowledge Check

True or False: Educating the diabetic resident is really all about what you have to say.

True

False

What to Teach

Describe diabetes: its causes, types, and pathophysiology. Review signs and symptoms of hypo- and hyperglycemia. Discuss the primary risk factors such as obesity, lack of exercise, smoking, and hereditary factors.

Most importantly, review life-style modifications and risk reduction. Describe the benefits of nutritional and weight management, as well as the benefits of physical activity. Explain the concept of tight glycemic control and its importance. Your goal should be to make sure the resident understands, as much as possible, the degree to which he or she has the responsibility – and the capability – to control the progress of the disease.

Blood Sugar Monitoring

f the resident will be responsible for self-monitoring, review basics such as skin cleanliness, rotation of the lancet testing site, and periodic recalibration of the device. Make sure the resident understands how often to conduct a blood sugar test. If four times a day, testing should be conducted before each meal and at bedtime. If twice a day, testing should be conducted before breakfast and supper. If once a day, testing should be conducted at different times during the day so that variances throughout a typical day can be detected. Explain corrective measures the resident can take if blood sugar levels fall outside of target range. If below 70, the resident should take some form of sugar followed by more complex carbohydrates. Explain what to do if administering sugar does not work. If above 200, the resident should follow prescribed parameters to readjust the regimen. If above 300, the resident should contact his or her physician to adjust the regimen. If above 400, the resident should contact a physician immediately.

Emphasize the importance of keeping a blood sugar diary for caregivers and family to review. Teach the resident what to do when ill, especially in the case of fever or inadequate food or fluid intake.

Knowledge Check

The resident should contact a physician immediately if blood sugar rises above:

- 400

- 300

- 200

- 100

Dietary Regularity

Make sure the resident is aware of the importance of taking regular meals. In addition advise the resident to eat more before taking on unusual levels of activity. Recommend that the resident take a bedtime snack and always keep a packet of sugar available.

Other Health Maintenance Information

Describe the frequency and importance of follow-up visits. The resident should be prepared for quarterly A1C tests, urine ketones and protein, and blood pressure. Describe semi-annual tests (BUN/CR&GFR, and urine albumin), and annual tests (LFTs and Lipids, vision, eye exam with dilatation).Encourage annual preventive dental care as well as proper dental hygiene to reduce the risk of decay and infection.

Review Foot Care

The resident should be taught how to inspect the foot daily for trauma, blisters, cuts, rashes, or changes in color. Shoes and clean socks should be worn at all times, and shoes should be checked for foreign objects every time. Feet should be washed and thoroughly dried, and moisturizer should be applied Ð but never between the toes. Exposure to hot water, heating pads or hot water bottles should be avoided, as should adhesive tape and tight or rolled-up hose. Procure quarterly podiatric care of nails and calluses, explain that the resident should never personally apply anything more forceful than emery boards or pumice stones. Advise the resident to avoid crossing his or her legs to prevent circulatory problems, and discourage smoking.

“Sick Days”

Teach residents what to do when ill, especially when they have a fever or are not taking in adequate food and fluids. Explain that they should check their blood glucose levels more frequently, and call their physician to find out if they should make any changes in medication regimens. Explain the importance of proper hydration, especially in the presence of fever.

Conclusion

End of Module 3, Unit 3.

Generally speaking, there’s a direct relationship between education and compliance. A better-informed patient is better equipped to take an active part in maintaining good habits and proper maintenance. Your role is to provide an atmosphere that nourishes a good relationship with the resident to encourage understanding.

Module 3, Unit 4 Introduction

We’ve all heard the old saying that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Nowhere, perhaps, is this saying more applicable than in the case of diabetes. Genetic predisposition certainly is a factor in the development of diabetes, but lifestyle choices play a huge part. This unit describes the “big 3” behaviors that have the biggest influence on the development – and progress – of diabetes.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- Describe the lifestyle-related causes of insulin resistance

- Define Medical Nutritional Therapy (MNT) and its goals

- Define “Gluconeogenesis”

- Explain the advantages of the “Consistent Carbohydrate Diet”

- Describe some of the barriers to dietary compliance and how to mitigate them

- Describe the health benefits of exercise in the diabetic resident

- List the parameters for developing an exercise program

The “Big 3”

Weight management, exercise, and smoking cessation are the “big 3.

Lack of exercise can exacerbate the problem. Exercise allows sugar to cross into muscle and fat, even in the absence of normal amounts of insulin. Weight loss and increased exercise can reverse the problem. Studies have shown that weight loss can reduce the risk of developing diabetes by as much as 58%25. Along with smoking cessation, weight management and routine exercise constitute the “big 3” of diabetes-moderating lifestyle changes.

Knowledge Check

In lifestyle modification for control of diabetes, the “big 3” are:

- Exercise, medication, and monitoring

- Medication, weight loss, and education

- Education, exercise, and smoking cessation&

- Exercise, weight loss, and smoking cessation

Weight Management

Encourage realistic dietary goals, including a regular diet with enough variety to maintain interest. Consistency is key, in both meal times and amounts of carbohydrates. Residents should also be advised on including appropriate amounts of fiber in the diet. Bear in mind that dietary restrictions may be detrimental to quality of life in a resident with few remaining pleasures. Discuss diet with the resident, family, and care team and strive to achieve a workable balance.

Medical Nutritional Therapy

Frequent small meals afford the body an opportunity to burn food as it comes in.

Medical Nutritional Therapy (MNT) begins with assessing an individual’s nutritional needs and then developing a dietary plan that best meets those needs. For the diabetic, the goals of MNT include attaining and maintaining a healthy body weight, controlling sugar spikes, and normalizing both blood pressure and lipids. MNT plays an important role in diabetes care. A well-planned diet, combined with a regular exercise program, can reduce reliance on medications as well as reduce the risk of diabetic co-morbidity.

Gluconeogenesis

Frequent small meals afford the body an opportunity to burn food as it comes in.

You may remember from earlier units that glucose is the body’s primary source of fuel. Glucose can be ingested directly; the body can also break down (metabolize) any form of food to use as fuel. Carbohydrate, protein, and fat can all be converted into glucose. The medical term for this process is Gluconeogenesis, from the Latin words for glucose, new, and create. Frequent small meals afford the body an opportunity to burn the food as it comes in instead of being overwhelmed and having to deal with higher levels of fuel than needed at any particular time.

Knowledge Check

True or False: Blood sugar can be better regulated by eating large meals at 6-hour intervals.

True

False

Carbohydrates, Fat, and Protein

A carbohydrate is either a starch or a sugar. Carbohydrates are made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen and are easily converted into glucose. Fat is also made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, but takes more time to break down into glucose. The body will consume energy from carbohydrates first. Then, if additional fuel is needed, the body will begin to burn fat. The acid byproducts of fat breakdown are called ketones. Excessive ketone levels lead to ketoacidosis, a potentially dangerous condition. For more information on ketoacidosis, see unit 2 of this module. Protein is made up of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. When the body resorts to using protein for fuel, it leaves nitrogen and can ultimately affect the Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) level.

Recommended Daily Intake Levels

Daily intake of carbohydrates should equal 45% to 65% of total calories. Fats are usually stored, and if not utilized will gradually build up in the storage areas of the body. Some fat is necessary in the diet but intake should be kept at less than 30%25 of total daily calories. Less than 10%25 of total daily calories should come from saturated fats. Protein is composed of amino acids, the essential “building blocks of life.” Protein intake should be about 10% to 20% of total daily calories.

The Consistent Carbohydrate Diet

The consistent carbohydrate diet prevents post-prandial glucose spikes.

In the past, it was thought that diabetics should restrict all simple sugars. In recent years, the focus has shifted to emphasize the total amount of carbohydrate in a meal rather than the source of the carbohydrate. The goal is to maintain a diet that has a consistent amount of carbohydrates from meal to meal and from day to day. The diet can include a variety of foods and should be tailored to the resident’s likes and dislikes. Desserts can be worked into a consistent carbohydrate meal plane. A “glycemic index” provides a measure of the relative impact a specific food will have on the blood glucose level. Foods that make glucose more readily available, such as simple sugars, have a higher glycemic index. The consistent carbohydrate diet prevents post-prandial (after meal) glucose spikes, thus reducing the risk of damage to the endothelial lining of the body’s capillaries.

Sodium

When considering the dietary needs of the diabetic resident, be aware of sodium as well. Remember that a frequent co-morbidity with diabetes is hypertension, and that sodium can impact cell membrane integrity. Foods that are high in sodium include many canned, processed and fast foods; pickles and olives; most snack foods; and frozen or packaged dinners. Sodium-heavy condiments such as soy sauce should be used sparingly.

Deprecated Diet Restrictions

The so-called ADA diet is no longer being used and the American Diabetes Association no longer endorses any single meal plan or specified percentages of macronutrients. Certain dietary restrictions, such as the absolute elimination of sweets, are also no longer considered appropriate. Keep in mind that intake and exercise are both important when addressing weight issues in the diabetic resident.

Knowledge Check

Which of the following items should be altogether excluded from the diabetic resident’s diet?

- Sodium

- Fat

- Sugar

- None of the above

Compliance Issues

An overly complex or restrictive diet is not likely to succeed.

When formulating dietary recommendations, take into account the resident’s likes and dislikes, as well as the resident’s need for some autonomy. Some residents feel that mealtime is one of their last remaining pleasures. Others have lost interest in food and struggle just to maintain adequate caloric intake. In either case, a diet that is overly complex or restrictive is not likely to succeed. Help the resident to understand the risks and benefits of his or her dietary choices. Whenever possible, include the family in decision-making and help them also to understand the resident’s needs.

Benefits of Exercise

Everyone, regardless of medical condition, benefits from regular exercise. For the diabetic, the benefits of exercise are even more pronounced. Exercise can reduce the health risks of diabetes, and may even prevent or delay the onset of the disease. Regular exercise improves metabolism and insulin effectiveness, reducing blood glucose levels. Coupled with a sensible diet, exercise can help reduce weight as well, which can be especially beneficial because excessive body fat inhibits the effectiveness of insulin. Exercise can also reduce the risk of diabetic co-morbidity, particularly atherosclerosis, by reducing blood cholesterol and lipid levels. Furthermore, exercise helps reduce stress and improves the feeling of well-being.

Exercise

For the diabetic resident, it is important to develop an exercise regimen with input from the care team. Discuss possible programs with the resident’s physician and/or rehabilitation team. Talk with the resident about his or her exercise preferences and encourage the resident to exercise with others who share those preferences. Any exercise routine should begin with a warm-up and stretching period and end with a cool-down. Keep duration between 20 and 45 minutes, five or six days per week.

Knowledge Check

True or False: Regular exercise improves insulin effectiveness, even after the period of exercise.

True

False

Exercise Precautions

Some precautions are wise. Ensure that the resident wears proper footwear. The resident should wear an alert device, if applicable, especially if exercising alone. Monitor blood glucose levels initially, both before and after exercise. If glucose is above 300 without ketosis, or above 250 with ketosis, exercise should be avoided. If glucose is below 100, add carbohydrates prior to exercise (or decrease diabetic medications if appropriate). Keep carbohydrates or sugar nearby, and monitor hydration. Avoid extreme temperatures as well.

Smoking Cessation

Smoking exacerbates complications of diabetes.

Smoking, even without diabetes, affects circulation. As such, smoking exacerbates micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Studies have also shown that smoking can contribute to insulin resistance. Smoking increases the risks of diabetic co-morbidities such as heart disease, stroke, and damage to the nerves, kidneys, and retinas. For those who are quitting, concerns about weight gain are common. These concerns are especially significant for diabetics who are also trying to manage their weight. Be sure to supply the resident with healthful substitute behaviors and foods.

Conclusion

End of Module 3, Unit 4

Diet and exercise play an important role in managing diabetes. A well-planned diet can reduce extreme changes in blood sugar and thereby reduce the risks associated with diabetes. Extreme restrictions, however, can have a negative effect, and such restrictions are no longer considered necessary. On the contrary, variation in the diet should be encouraged. As with diet, exercise can have beneficial effects on disease management. An exercise plan should take into account the resident’s preferences, and should be designed with safety and consistency in mind. Finally, if the resident smokes, explain the additional health risks of smoking and help develop a smoking cessation plan.

Module 3, Unit 5 Introduction

Although diabetes is linked to multiple co-morbidities, there is much that can be done to prevent or diminish its effects. Good practice covers a wide range of interventions including screenings, systemic approaches, and treatments targeted at specific issues. This unit provides guidelines for assessing and monitoring the resident’s condition and for prevention and/or treatment of various co-morbidities.

Objectives

By the end of this unit, you will be able to:

- List assessments that should be performed on admission, at annual or semi-annual intervals, and on a regular basis

- Describe interventions for a variety of diabetic co-morbidities

Assessments at Time of Admission

Upon or shortly following admission, the following tests should be performed to obtain baseline values.

- Vision screening with dilated funduscopic exam

- Signs and symptoms of CHF or angina

- ABI

- EKG

- Lipid panel

- LFT

Annual and Semi-annual Screenings

Periodically, residents should receive the following screenings:

- Annual vision with dilated funduscopic exam

- Annual dental, including gum, tongue and mucosal exam

- Semi-annual E-panel including BUN/Cr

- Lipid panel as indicated

- Serum amylase or lipase within six months of admission

- Urine albumin and hemoglobin

Regular Monitoring

More frequent monitoring should include:

- Question resident about development of visual floaters or increased blurriness

- Assessment for gum disease

- Regular BP monitoring

- Watch for fungal infections

- Capillary filing and pedal pulses

- Orthostatic hypotension (fall prevention)

Knowledge Check

Which of the following should be performed more often than twice a year?

- Vision with dilated funduscopic exam

- Blood Pressure monitoring

- Urine albumin and hemoglobin check

- EKG

Retinopathy Interventions

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among Americans.

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among Americans. Fortunately, vigorous glucose control can reduce the severity of retinopathy as well as delay its onset. Blood pressure control is preventive as well, as is glaucoma control. A person with diabetes is nearly twice as likely to develop glaucoma as a person without diabetes. If blood vessels begin to leak or proliferate, surgical intervention may be recommended. Laser photocoagulation may be used to seal leaking vessels or to shrink or destroy abnormal ones. Vitrectomy may be used to remove blood in the eye’s vitreous gel.

Cardiovascular Interventions

Cardiovascular diseases are a major cause of mortality in residents with diabetes. As with so many diabetic co-morbidities, diligent blood pressure management is key. Aim for blood pressure of 120/80. Address signs and symptoms of Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) or angina quickly: watch for increased fluid retention, chest pain, and/or shortness of breath (dyspnea) with activity. Diabetic patients may be prescribed low-dosage aspirin therapy: there is no evidence that aspirin use increases the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Statins, ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers may be prescribed as well, unless otherwise contraindicated. ACE inhibitors and ARBs have both been shown to be kidney protective. Note however that ACE inhibitors may increase potassium retention, which may be detrimental in residents with end-stage renal disease. Beta blockers and thiazide diuretics may cause an increase in the incidence of diabetes. Also note that African Americans tend to be less responsive to Beta blockers and ACE inhibitors.

Nephropathy Interventions